The Marburg virus or MARV is a virus that comes from the Filoviridae family of viruses alongside the Cuevavirus and the Ebolavirus. Similar to Ebola, which causes the Ebola virus disease or EVD and is responsible for several Ebola outbreaks across the world, Marburg is a hemorrhagic fever virus that causes the Marburg virus disease or MVD.

Note that the World Health Organization has categorized the Marburg virus as a Risk Group 4 Pathogen while the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the United States Department of Health and Human Services ranks it as a Category A Priority Pathogen. Several cases of MVD outbreaks have been documented across the world.

A Look Into the Origin of the Marburg Virus: Where Does it Come From and How Did it Infect Humans?

Discovery of the Virus and the First Recorded Outbreak

The Marburg virus has been regarded as an extremely dangerous pathogen that can cause severe fever and internal hemorrhages in humans and non-human primates. The clinical presentation of the resulting MVD is similar to the Ebola virus disease.

Of course, considering its dangers to human lives and human communities, it is interesting to understand how did it infect humans in the first place. Where does the Marburg virus come from? When did it first infect humans?

The virus was first discovered at the Philipps University of Marburg in Germany in 1967 when researchers and laboratory technicians showed symptoms of hemorrhagic fever. These workers handled tissue samples from African green monkeys that were imported from Uganda to Germany and the former Yugoslavia for research purposes.

Several laboratories were working on a vaccine against the disabling and life-threatening poliovirus. Part of their research was to obtain kidney cells from imported deceased monkeys to culture viral strains and develop a specific poliomyelitis vaccine.

Researchers in another laboratory in Frankfurt who handled samples from imported African green monkeys were also infected. An outbreak soon ensued following the exposure of lab workers. 31 individuals developed a severe disease and 7 of them died.

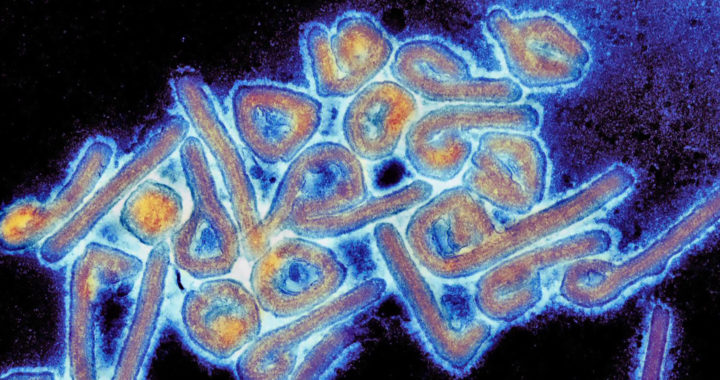

A cooperative effort of researchers from Marburg and Hamburg headed by R. Siegert succeeded in isolating the etiologic agent in less than three months since the outbreak was documented. This was later confirmed by C. Kunz et al. and R. E. Kissing et al. The virus was described to be 90 to 100 nanometers in diameter and 130 to 2600 nanometers in length.

Pinpointing Further the Origin and Ecology of the Virus

Note that the ebolavirus was identified in Africa in 1976. It was later classified under the Filoviridae family of viruses together with the Marburg virus. Several cases and sporadic outbreaks of MVD emerged in Africa from 1975 to 1985.

Ecological niche modeling studies conducted by Peterson et al. later revealed that the Ebola virus is endemic in the rainforests of central and western Africa while the Marburg virus is prevalent in open and dry areas of the eastern and south-central regions of Africa.

Further studies concluded that Egyptian fruit bats or R. aegyptiacus are the natural reservoirs. These animals harbor the Marburg virus in their bodies without getting ill. Other animals exposed to these bats can become carriers. It is unclear when exactly the virus first infected humans but the outbreak in Germany remains the first documented case.

Nevertheless, considering how the virus affects humans, the Marburg virus disease is also considered a zoonotic disease and a product of a spillover phenomenon in which a pathogen jumps from an animal host to a human host through exposure or contact.

There are different routes and factors that could have enabled the virus to infect humans. Examples of routes are direct and indirect zoonosis or direct and indirect transmission. Animal handling and wildlife-human interactions are notable transmission factors.

Several studies showed that most primary infections that resulted in MVD outbreaks were linked to human activities that involved entering caves where fruit bats dwell. These activities involved mining or some form of tourism or cave exploration. Human-to-human transmission is also possible via body fluids through unprotected sex and broken skin. Photo credit: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston / Adapted / CC BY-SA 4.0

FURTHER READINGS AND REFERENCES

- Brauburger, K., Hume, A. J., Mühlberger, E., and Olejnik, J. 2012. “Forty-Five Years of Marburg Virus Research.” Viruses. 4(10): 1878-1927. DOI: 3390/v4101878

- Kissling, R. E., Robinson, R. Q., Murphy, F. A., and Whitfield, S. G. 1968. “Agent of Disease Contracted from Green Monkeys.” Science. 160(3830): 888-890. DOI: 1126/science.160.3830.888

- Kunz, C., Hofmann, H., Kovac, W., and Stockinger, L. 1968. “Biological and Morphological Characteristics of the ‘Hemorrhagic Fever’ Virus Occurring in Germany.” Wiener Klinische Whochenschrift. 80(9): 161-162. PMID: 5688605

- Peterson, A. T., Carroll, D. S., Mills, J. N., and Johnson, K. M. 2004. “Potential Mammalian Filovirus Reservoirs.” Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10(2): 2073-2081. DOI: 3201/eid1012.040346

- Peterson, A. T., Lash, R. R., Carroll, D. S., and Johnson, K. M. 2006. “Geographic Potential for Outbreaks of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever.” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 75(1): 9-15. DOI: 4269/ajtmh.2006.75.1.0750009

- Siegert R., Shu H. L., Slenczka H. L., Peters D., and Müller G. 1968. “The Aetiology of an Unknown Human Infection Transmitted by Monkeys.” German Medical 13(1): 2. PMID: 4968593