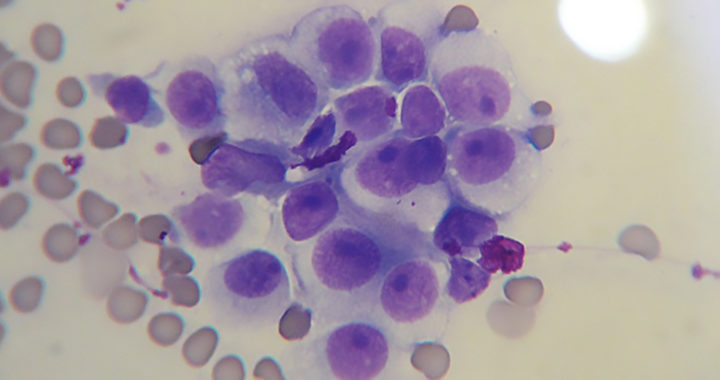

The canine transmissible venereal tumor is a rare type of cancer that affects dogs. It is also referred to as canine transmissible venereal sarcoma, sticker tumors, or infectious sarcoma. This disease affects mainly the external genitalia of dogs and their mouth or nose in some rare cases,. The cancer results in the appearance of a grotesque-looking, cauliflower-like tumor.

Furthermore, when affecting the penis or prepuce of male dogs, or the vagina or labia of female dogs, the review study by Utpal Das and Arpu Kumar Das mentioned that the disease can cause discharge and urinary retention. On the other hand, when affecting the facial area, the study of L. G. Papazoglou et al. notedthat the disease causes nosebleeds and other nasal discharge, fistulae, facial swelling, and/or enlargement of the submandibular lymph nodes.

Canine transmissible venereal tumor affects a considerable number of dog populations across the world. It is still considered rare simply because it is a transmissible disease. Note that all dogs with this disease have acquired cancer cells that descended from a single or several cancerous cells that emerged in a single ancestral dog about 11000 years ago.

Explaining Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: Ancient Cancerous Cells that Can Infect Other Dogs

Understanding Transmissible Cancer in Dogs

Cancers emerge when a single cell in the body acquires mutations that result in an uncontrolled cellular division that further leads to tumors. These cells then spread to different parts of the body through a process called metastasis. Cancer is not normally contagious. It is very rare for cancer cells to leave the bodies of their hosts and spread to other individuals.

Some extremely rare types of cancer can be contagious. There are currently four known cases of parasitic or transmissible cancers. These are the devil facial tumor disease affecting Tasmanian devils, contagious reticulum cell sarcoma affecting Syrian hamsters, leukemia affecting soft-shell clams, and the canine transmissible venereal tumor affecting dogs.

Nevertheless, in transmissible cancers, the cancer cells are themselves the infectious agents, and the tumors that form are not genetically related to the affected organism. Thus, in the case of a dog suffering from the canine transmissible venereal tumor, the disease is a result of external cancer cells entering its body and spreading through its organs and tissues.

The canine transmissible venereal tumor is transmitted through sex or contact with the affected areas. It can also infect other canid species like foxes and coyotes. S. Mukaratiwa and E. Gruys noted that this disease is unique because it is the only known naturally occurring cancer that can be transplanted as an allograft between different dogs other members of the canid family.

Mukaratiwa and Gruys added that the progression of cancer follows a predictable growth pattern observed both in natural and experimental cases. The cancer would enter an initial growth phase lasting for four to six months, followed by a stable phase, and a regression phase. Metastasis is a rare occurrence except for puppies and immunocompromised dogs.

Researchers Clare A. Rebecca et al. mentioned that the cancerous cells in canine transmissible venereal tumor are now collectively and essentially living as a unicellular and asexually reproducing pathogen. Remember that the particular cancer cell is an infectious agent and the tumor or cancerous tissues it creates are genetically unrelated to the affected host organism.

The Oldest Continuously Surviving Cancer

A genomic sequence analysis by Rebecca et al. revealed that the original cancer cell emerged from a dog or a wolf more than 6000 years ago. Additional findings from another genomic sequence analysis by Andrea Strakova and Elizabeth P. Murchison further revealed that the cancer cell first emerged about 11000 years ago from the somatic cells of an individual dog.

The cell acquired several adaptations or mutations that made it transmittable between hosts. It also acquiring a genome configuration that makes it compatible for long-term survival as an allogeneic graft. The process in which it infects can be likened to a successful organ transplant. It has evolved to be less likely to be rejected by the immune system of its new host.

Researchers Elizabeth P. Murchison et al. provided several hypothetical insights. One is that the first cancer cell survived the death of the ancestral dog and was transmitted to another dog through sexual intercourse. The cell had already developed necessary adaptations needed to survive in an external environment and thrive and replicated in another host.

A genomic sequence analysis of cancer cell samples obtained from different continents also showed that the first population of cancer cells initially existed in one isolated population of dogs for most of its history. The wider global transmission was likely to have occurred within the last 500 years when seafarers and explorers had brought in dogs in their global expeditions.

It is also worth mentioning that the genomic sequence analysis performed by Murchison et al. revealed that the present cancer cells carry about two million mutations. Note that human cancer cells carry between 1000 to 5000 mutations. The higher number of mutations suggest that the cancer cells in canine transmissible venereal tumor for a longer time.

Nonetheless, apart from being one of the rare types of transmissible cancer, the canine transmissible venereal tumor remains intriguing and significant because it is the oldest continuously surviving cancer. Studying the genetic make up of the involved cancer cells could provide valuable insights into the fundamental processes of cancer development and evolution.

FURTHER READINGS AND REFERENCES

- Das, U. and Das, A. K. 2000. “Review of Canine Transmissible Venereal Sarcoma.” Veterinary Research Communications. 24(8): 545-556. DOI: 1023/a:1006491918910

- Mukaratirwa, S. and Gruys, E. 2003. “Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour: Cytogenetic Origin, Immunophenotype, and Immunobiology. A Review.” Veterinary Quarterly. 25(3): 101-111. DOI: 1080/01652176.2003.9695151

- Murchison, E. P., Wedge, D. C., Alexandrov, L. B., Fu, B., Martincorena, I., Ning, Z., Tubio, J. M. C., Werner, E. I., Allen, J., De Nardi, A. B., Donelan, E. M., Marino, G., Fassati, A., Campbell, P. J., Yang, F., Burt, A., Weiss, R. A., and Stratton, M. R. 2014. “Transmissible Dog Cancer Genome Reveals the Origin and History of an Ancient Cell Lineage.” Science. 343(6169): 437-440. DOI: 1126/science.1247167

- Papazoglou, L. G., Koutinas, A. F., Plevraki, A. G., and Tontis, D. 2001. “Primary Intranasal Transmissible Venereal Tumour in the Dog: A Retrospective Study of Six Spontaneous Cases.” Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A. 48(7): 391-400. DOI: 1046/j.1439-0442.2001.00361.x

- Rebbeck, C. A., Thomas, R., Breen, M., Leroi, A. M., and Burt, A. 2009. “Origins and Evolution of a Transmissible Cancer.” Evolution. 63(9): 2340-2349. DOI: 1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00724.x

- Strakova, A. and Murchison, E. P. 2015. “The Cancer Which Survived: Insights from the Genome of an 11000 Year-Old Cancer.” Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 30: 49-55. DOI: 1016/j.gde.2015.03.005